Description

Humans consider themselves to be ranked among the most intelligent of living creatures and therefore maintain that of all species they themselves possess the greatest potential. If this is true, it is precisely because we possess the most active imaginations. Man, as Gaston Bachelard observed, is an imagining being, and imagination is the highest form of intelligence. We celebrate imagination in children, but think nothing of the fact that it often wastes away in adults.

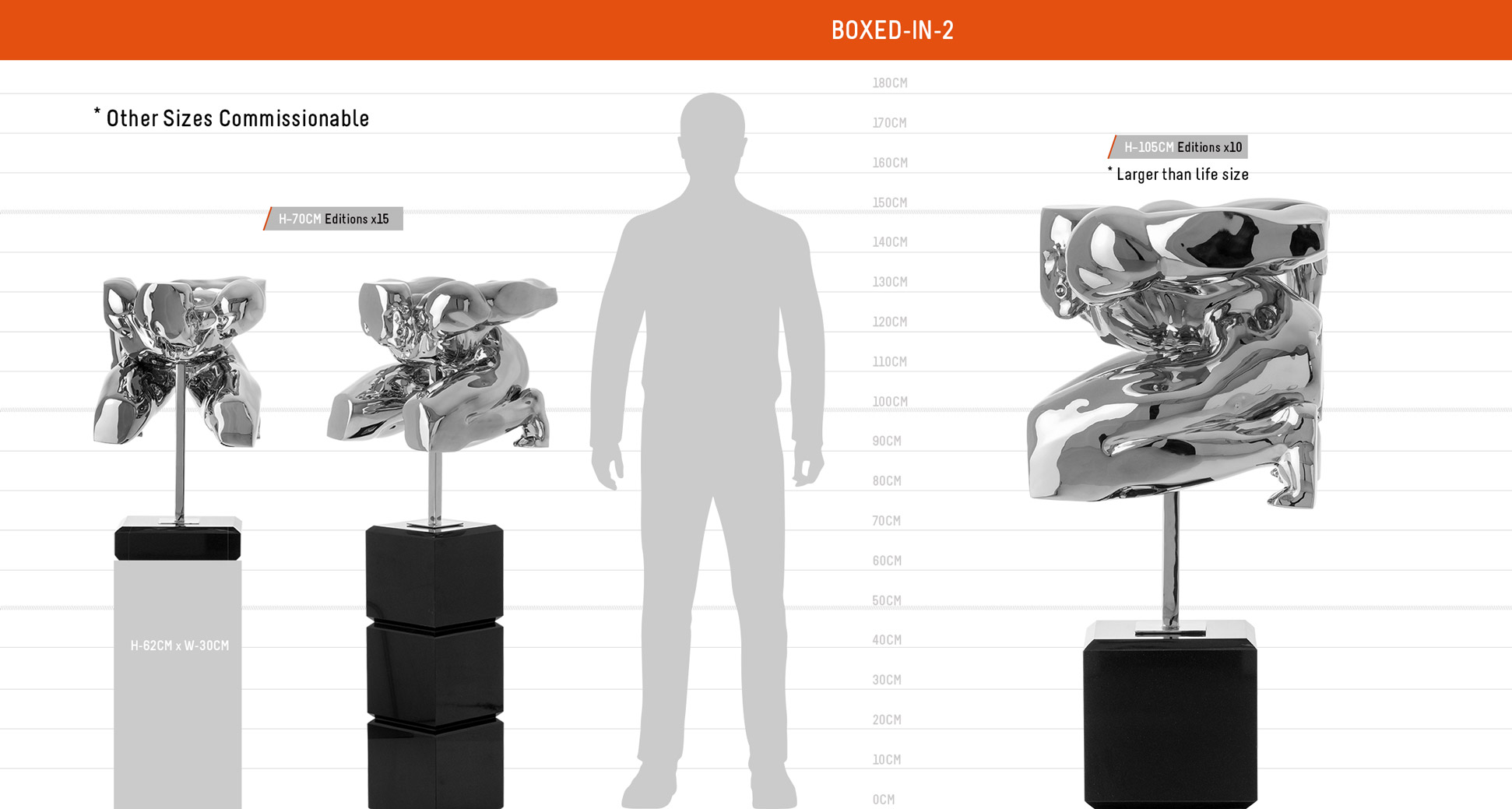

Boxed-In No. 2—Invisible Boundaries, Unbounded Potential

We often tout humanity’s intellect as our greatest advantage among living creatures. Yet “Boxed-In No. 2” invites us to question how we harness that intelligence, pointing to an apparent paradox: despite possessing expansive imaginations, adults frequently stifle their creativity behind invisible barriers. This human boundless creativity stainless sculpture clarifies that our greatest potential arises from imaginative leaps—those spaces unconfined by routine or expectation.

On Invisible Boundaries—Man’s Boundless Potential According to Bachelard

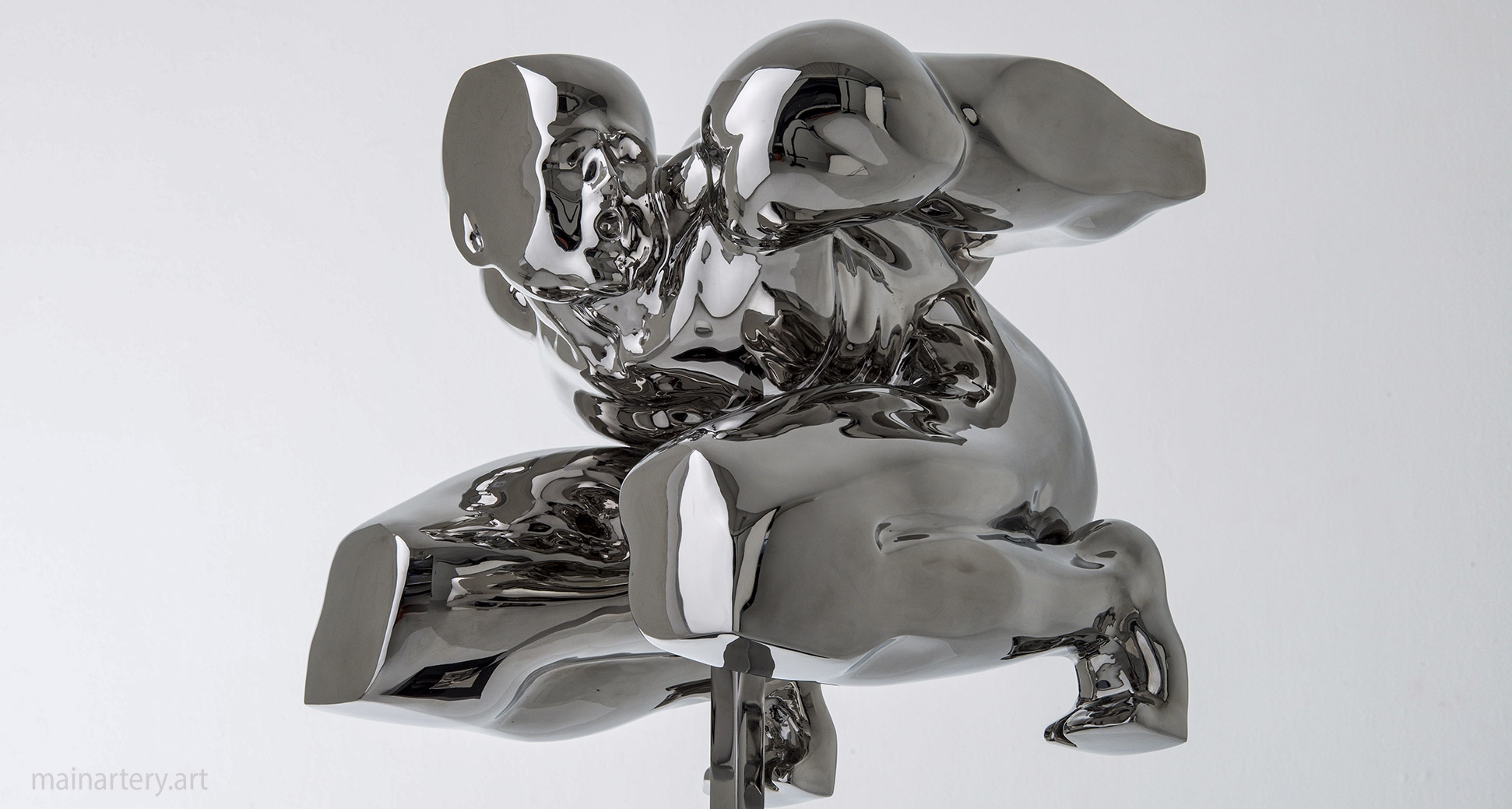

Philosopher Gaston Bachelard famously characterized humans as “imagining beings,” insisting that imagination ascends to the highest form of intelligence. The sculpture resonates with this conviction by depicting a figure poised within—or perhaps pushing against—a shape or boundary. Are these walls a literal box confining the subject? Or do they represent intangible restrictions—societal norms, self-doubt, or the inertia of habit? The piece stands as a conversation-starter about how invisible constraints can hamper our potential, ironically thwarting the creative edge that sets humankind apart.

A Paradoxical Construction—Invisible Borders and Inherent Freedom

While physically rendered in stainless steel, “Boxed-In No. 2” hints at unseeable constraints more powerful than any tangible cage. The figure’s posture, partially contorted or pressed against sleek, reflective surfaces, underscores the tension between aspiration and limitation. By making the box walls transparent or implied, the sculpture underscores that many boundaries exist only in our minds—outdated beliefs, internalized fears, or inherited rules. Viewers might feel a sense of longing as they witness the figure either striving to escape or forced into partial compliance.

In adult life, as the narrative suggests, imagination often wanes under pressure from daily responsibilities and social expectations. Childhood’s freewheeling creativity diminishes in the face of “practical concerns.” The sculpture critiques this loss, reminding us that an “imagining being” can reshape reality, whether through art, innovation, or altruistic vision. If we fail to nurture that capacity, we box ourselves into narrower experiences, forfeiting the limitless playground that once defined childhood curiosity.

Placed in a corporate environment, “Boxed-In No. 2” might prompt employees to question standard procedures or spark novel solutions. In a public gallery, it could inspire individuals to reevaluate personal or cultural norms. The luminous steel surfaces reflect onlookers’ faces, forging a direct link between the viewer’s self-image and the piece’s metaphorical statement. Each reflection becomes an invitation to introspect, to identify where one’s mental boxes lie.

Ultimately, “Boxed-In No. 2” affirms that genuine progress—for societies and individuals—emerges from a willingness to surpass perceived limitations. The piece encourages an embracing of creativity not merely as a childhood fancy but as the pinnacle of intelligence. By capturing the moment of tension between boundless potential and invisible restraint, the sculpture resonates with universal struggles: the pull between comfort and risk, conformity and brilliance, stasis and growth. Through art’s lens, we glimpse that freedom is as close as our willingness to question the very walls we’ve let confine us, reaffirming that an unshackled imagination is indeed our deepest well of power.